Bullpush Hollow–An Online historical Graphic Novel

new strips updating twice weekly

Chapter 1 — Beginnings

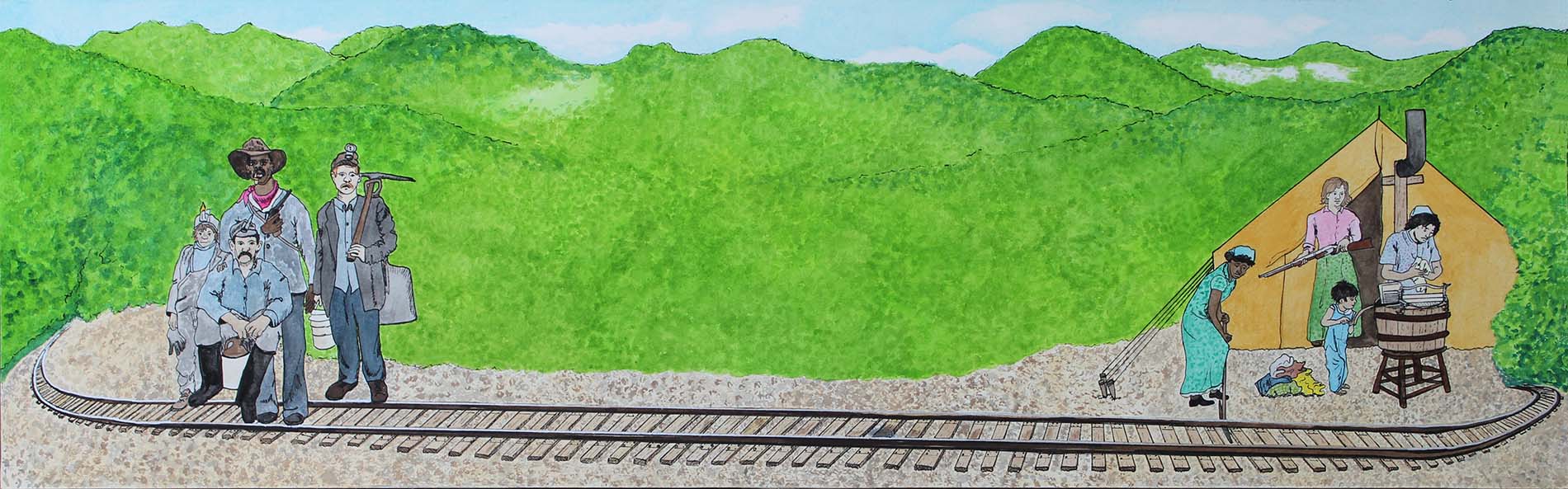

Cannelton West Virginia, 1907

Main Sources for #2: M. Glass, Cavalier, Gillespie Oral History, Interviews

Endings and Beginnings #2A

Historical Notes

Like many people living on company property, neither Margaret Johnson, who ran the boarding house, nor CC show up in Fayette County census records for 1910 or the years afterwards. CC does show up in census records with his father, even when not living in the household and then again once he lives on private property, but as she lived in the same area for the rest of her life, Margaret never does. (Yes, she existed. We’ve got pictures!)

extra story, history, news articles, and pictures available exclusively on Patreon!

The Cannelton boarding house built in 1926 is still standing and still in use as rental units. The one used in 1907 is long gone. Since owners and their representatives might stay there, boarding houses were white or *Italian only. There were different ideas about who was ‘white’ at the time. Additionally race relations in the mines were not exactly what they were elsewhere. Miners of all races were viewed by mine owners as ‘servants’ and for miners the basic reality of social associations was one of class rather than race.

While mine owners treated miners more as assets than employees, they often saw promoting segregation of community living as a means to prevent successful unionization. Schools were segregated by state law.** Neighborhoods were segregated in some company towns and not in others depending upon the owner’s policies.

The mining camps around Cannelton were not segregated. Some mine owners bunked more single black miners per shack than white miners per shack; others made no distinction. Segregated or not, non-unionized company housing was substandard regardless of race with shacks being post rather than foundation constructed, one hand pump well per five or more houses, outdoor coal fired cooking, and surface privies which spilled human waste out onto the ground.

Pay was universally the same, and the attitude of ‘everyone is black in the mines’ was common–we’re not technically property but we’re all being treated as such. As George Echols, a former slave and union local vice president, said to a senate investigative committee: “I know the time when I was a slave and I felt just like we feel now.”***

Owners claimed in court a master and servant relationship rather than an employer/employee – landlord/tenant relationship and workers took common cause in class and associated freely. Contemporary black, white, and immigrant miners who embraced unionism often reflected these attitudes. Black and immigrant miners were as likely (as a percentage of the population) to be elected to serve as local union officials as white miners. The same cannot be said of unions on a national level where the senior officers were more likely to be white. (Cavalier, Corbin [Life], Lane, 1913 Senate Paint Creek Hearings)

*Colloquially many white Appalachian miners of Fayette and Kanawha at the time might lump Eastern European and Italian immigrants together as ‘Italian’ when speaking unless specifically identifying an individual’s history.

**Paradoxically, segregated school policy in the very early 1900s may have resulted in employing black teachers that were much more qualified than the teachers at white schools in some coal camps. Unlike many states with segregated schools, West Virginia had a step pay system based on the highest degree a teacher had obtained without regard to race. This, along with the coal operators’ hands off education policies, attracted highly qualified black teachers to coal camp schools. By the early nineteen hundreds, it was not not uncommon for a white school to be taught by a high school graduate while the camp’s black school had a teacher with a master’s degree. Where statistics are available, black children had higher attendance rates than white children in the same communities. (Corbin [Life] 70-75, Lane, Clopper [Child Labor, 1908]).

Over the next twenty years this situation reversed. As the black population of the state increased, so did the prevalence of the KKK. State spending for segregated education did not keep pace and the legal requirement of equal pay for teachers was ignored. With poorly prepared teachers making as little as $20 a month and fewer schools, many children had no opportunity for education at all. [Trotter]

***George Echols’s full statement is comprehensive, eloquent and enlightening. We’ll focus on it and his story when we make it to 1921.

Since this post has meandered into the territory, you might consider pursuing our difficult topics page if you want to know how Bullpush Hollow approaches such things.

CC and Margaret Johnson much later in life.