A True Story–but what does that mean?

Whenever I see the claim “true story”, I have to research to see exactly what that means. What parts of the story are fictionalized for dramatic effect? What biases are built into the story? How close does it hew to known history?

Feel free to research this story in the same manner. In fact, I encourage you to do so. This story is important both as history and for the light it can shed on current events as well as human nature.

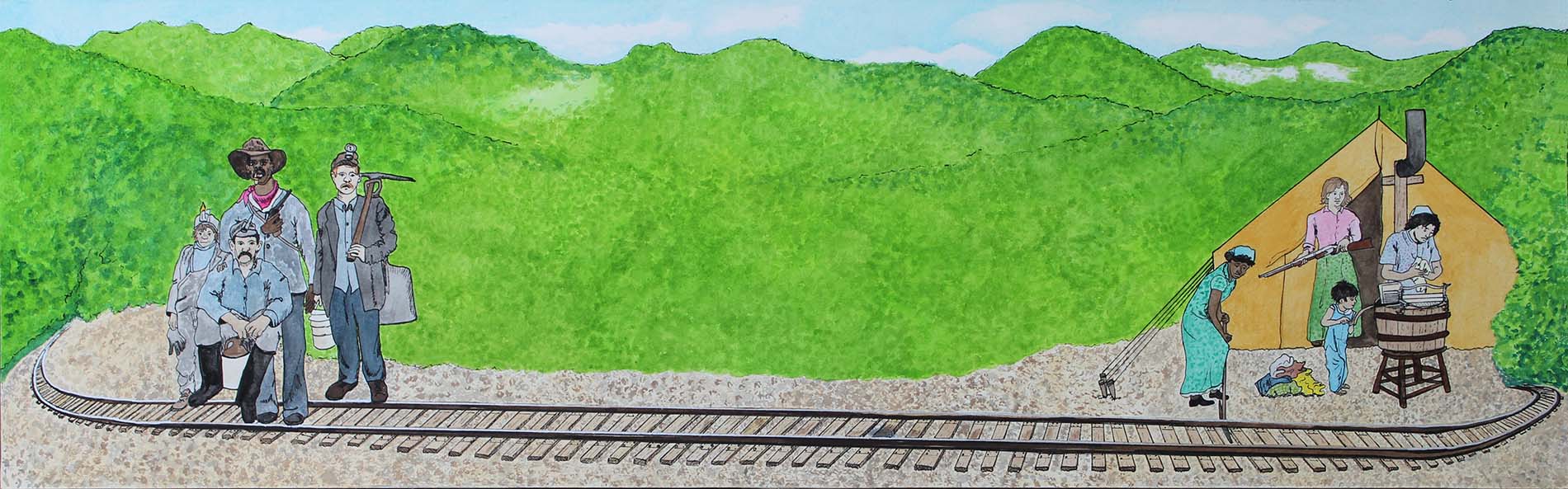

Let me help you get started by sharing some of my methodology. My intent, in telling this story, is to relate an accurate history of the lives and circumstances of West Virginia miners and their families in the early 1900’s from the perspective of the miners themselves–using their own voices and words whenever possible.

All continuing characters are real people whose stories follow known events. When possible, named characters are real people even when they appear for only a minor scene. All scenes, without exception, are based on the historical record. If there is a romance or a battle, the details of it aren’t included unless they are known or can be inferred from what we do know. No events are made up out of thin air for dramatic effect.

That said, availability of direct dialogue or play by play analysis type reporting in a given situation is rare except when reporting shocking or major events. Gun battles and public confrontations were occasionally, but not always, preserved with this level of detail. In the rare cases that conversations were preserved verbatim I use the speaker’s own words. Conversations are usually my creations intended to give life to the history while being derived from things we know. Occasionally we know what actions were taken, but not the specific names of all involved. In that case, who do we know was around and which of these people could plausibly have been part of this event?

Another challenge can be the euphemistic language of the day used when reporting on certain crimes. “Brutalities”, “depredations”, “ravishings”, and “horrors” against women and children are repeatedly reported as are things like “murder and worse”. The details of these attacks aren’t generally spelled out* in contemporary reporting. Rather, we are expected to read between the lines.

When sources disagree, which they often do, I try to:

- Identify the likely facts by comparing sources, seeking corroborating information, looking at motivations, considering how reliable the narrator’s sources are, considering the time passed between the event and reporting, and looking at bias.

- Keep in mind that I’m telling the story of the miners themselves.

- Stick to an account as true to the facts as possible even when it conflicts with number 2. Generally, it doesn’t. I’m not trying to create heroes and villains for the sake of a narrative or message. The question is “What happened?”

- When the above doesn’t flesh out a clear answer, make a judgment call. One example of this is whether Maud Estep picked up a gun and fired back at the train full of guards that had killed her husband with a Gatling gun. Her senate testimony says no. Other accounts say yes and include details of her words and actions. The details lend credence to other accounts, but the testimony disputes it. One of these is more interesting and while it is very clear who the aggressors were here, it is very plausible that she would want to leave that detail out in a hearing.

There is an amazing amount of oral and written documentation available that allows this approach. I’ve combed through a large list of sources as I researched for this story and continue to do so as I write. Just a few of the major sources are:

- Glass family oral and written history as compiled by Mary Glass and to an extent by myself. Anytime a character has the last name Gillespie, Cooper, or Glass they are related to me in some way.

- Thousands of period newspaper and periodical articles reporting on these events. The leanings of these papers vary widely (including actually changing facts of events) and the leanings themselves **add to the understanding of the history.

- A 1913 Senate Investigation and a later investigation following Matewan and Blair Mt.

- Public Records–births, deaths, marriages, censuses, property, etc.

- The Autobiography of Fred Mooney

- The works of

- David Corbin (extensive WV coal history research and writing)

- Winthrop Lane (contemporary investigative journalist and book author)

- And John Cavalier (Fayette County historian)

This is by no means a complete or even partially complete list of sources or authors used. Rather these are some of the sources that, at the time of this writing, have been relied on most heavily in creating the narrative.

Is it a true story? As much as we could make it, yes!

So research away, and if you want more–full sources, pictures, audio, or even my hundreds (by the end maybe thousands?) of pages of notes support us on Patreon for access!

–john

*Exceptions to this include reports of evictions during childbirth, shootings, forcing young women off the road and into the water to get them to raise and/or wet their dresses, beating pregnant women causing miscarriages, throwing babies, and one report of cutting off breasts. Usually, however, and universally in newspapers, the details are left very vague.

**A further note on newspaper sources: While newspaper articles include important information, what gets reported and by whom matters. Most of the goings on in the mining camps went unreported and unremarked upon. When it was reported, reporting was selective.

Most major papers were owned by people who also owned or operated mines. This was true both locally and nationally. Members of the AP board of directors were mine owners. These papers tended to depict miners as dependent and ungrateful, mine camp life as better than city life, and owners as benefactors. They generally reported miner hostilities and not guard hostilities.

On the other hand, explicitly pro-labor and socialist papers, would present the miner’s side of the story, occasionally claiming all hostilities were from the owner’s side but generally (particularly in the case of stories originating from WV and Chicago labor/socialist papers) laying out the grievances that precipitated the violence.

Findings from the senate hearing bore out the pro-miner version of events, more than the owner version. In either case, papers universally chose stories and parts of stories with the intent to persuade and much of the drama and preceding impetus for actions remain obscure to the casual news reader of the day. For later generations, while much information is lost, there is an opportunity to use newspaper reporting to gain insight into the motives and actions of various parties, and glean details and chronology while cross-checking reporting with demographic records, election results, company records, government reports, oral history, senate testimony, and other sources.