Wait, West Virginia Miners, the Original Rednecks, Were Socialist?

That doesn’t seem right.

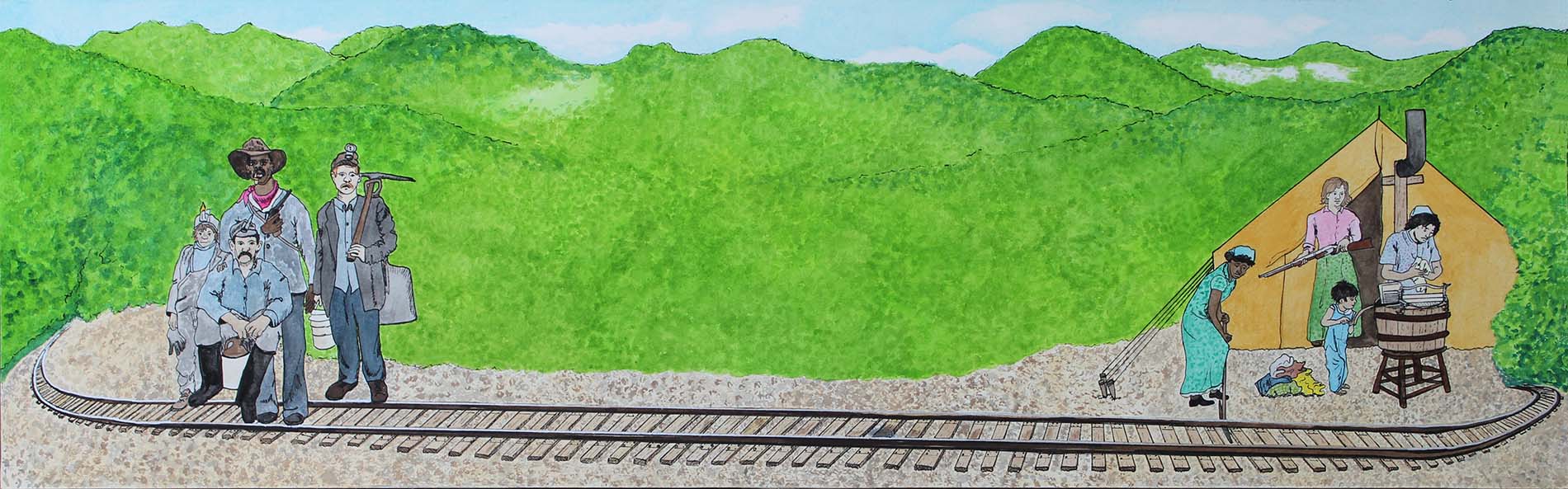

Let’s start with ‘rednecks’. It has been argued that the the term originated in my native state of West Virginia. There are numerous sources claiming that the term redneck originated as a description of rural miners marching to Matewan and the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921 due to the red bandannas they wore. At this time newspapers and even government officials referred to the group as rednecks.

The term actually predates these references. Earlier in American history, it had occasionally been used colloquially to reference either tories or Catholics. There is also evidence to support its use in the 1800s to refer to rural white farmers. These references are local and occasional in literature of the time.

However the use of the term redneck in period media begins to increase starting with the Paint and Cabin Creek War of 1912-1913 and can be found in socialist-leaning publications of the time. By the time of the battle of Blair Mountain, the term can be found in national publications referring to rural miners–immigrants, black, and white–who were fighting for labor and civil rights. Coal operators and writers of the time tied red bandanas worn as uniforms by backwoods militant miners during the coal wars to the term. It is also used pejoratively in association with descriptors like radicals, communists, socialists, and even anarchists.

So, yes West Virginia coal miners are associated with the increasing popular usage of ‘redneck’, but was redneck also a political term associated with socialism? Were the original redneck miners socialists?

James Green in his Book The Devil is Here in These Hills, argues that certainly–yes they were. Socialist and capitalist papers of the time period make the same claims with very different slants. Both of these news sources often credit outside socialists with causing the miner’s struggle against operators and the guard system. Miners themselves made it clear that this struggle was their own and that they, not outsiders, were their own agents of action.

During the Paint Creek war, prominent socialists such as Mother Jones, Ralph Chaplin, Harold Houston, and W.H. Thompson rallied and supported local miners who saw socialism as central to their struggle. During this time, strike and battle leaders such as Fred Mooney, Frank Keeney, and Few Clothes Johnson spoke openly of socialist ideals when rallying fellow miners.

David Corbin, a meticulous researcher of miner history, argues that they weren’t socialists–not really*. He suggests that miner association with socialism was more alliance than adherence. Corbin describes miner action as a cause without a defined and coherent philosophy. Certainly, socialists and miners worked together and many miners were, for a time, socialists–but it didn’t stay that way. He rightly points out that support for socialists dropped in 1913 after Eugene Debs of the Socialist Party of America (SPA) praised Governor Hatfield and endorsed a mandated settlement that left socialist activists and miners in prison and forced those who did not accept the terms out of the state at gunpoint. Mother Jones was one of the deported. Support for socialists in the state dropped. Many miners felt that now, they had to go it on their own.

So–were they or weren’t they?

To answer, first of all, we need to talk about socialist politics in this period. US socialists at the time fell largely into two camps: Direct Action and Boring Within.

Those who subscribed to boring within wanted to form alliances with existing pro-labor movements and other organizations with the goal of moving them and their members towards socialism. Boring within preached gradualism and compromise.

Direct action proposed that socialism could never be achieved by gradualism and that opposing serious injustices now, at times, required–well–direct action. New systems needed to be advocated for and established. Violence could be justified if it was necessary to secure worker rights or advance the cause of socialism.

The struggle in West Virginia illuminated and exacerbated this split. Local and national socialists of the direct action variety saw the oppression of mine camps as intolerable and the miner’s fight against capitalists, censorship, company stores, the mine guard system, and peonage as inevitable and necessary. They supplied weapons and logistic support to miners as they fought guards.

Local capitalist and socialist papers highlighted this association. Socialists were arrested. Presses were destroyed. National papers of both varieties picked up and spread this news. Socialists who subscribed to direct action emphasized the injustices miners were fighting and the necessity of their cause while boring within-ers bemoaned the miner’s fate but tried to distance themselves and at times the miners from the violence.

The national debate among socialists over violence and settlement in the coal fields became heated and personal. Socialist newspaper editors who had been imprisoned for supporting miners and abandoned by Debs gained a national following as they and Debs traded arguments, accusations, barbs, and insults. These debates expanded to the point that Debs, recently the public face of the party, attacked Chicago socialists in general as ‘so-called’ socialists and general public support for the party dropped as those within it splintered into factions.

In this context, when miners supported socialism and took action, they tended to be firmly in the direct action camp. Indeed, their actions opposing the guard system were driving the national debate. A black direct action miner who was one of the leaders of the Cabin Creek War, Dan Chain aka Few Clothes Johnson, was reported to have said while imprisoned at Moundsville: “I’s a better socialist than I ever was.” Frank Keeney, a white miner leader, also repeatedly identified publicly as a socialist. Many Italian miner organizers were also openly socialists.

In 1909, a group of rebelling Italian miners, who successfully prevented the implementation of the long ton and the use of Baldwin Felts agents in Boomer, identified their cause with anarcho-syndicalism. In 1912, these same Italian miners, allying with local socialists, used their organizational skills and experience with armed resistance to provide weapons and manpower to the miners of Paint and Cabin Creek who were striking, in part, to achieve these same goals.**

That doesn’t mean that all redneck miners were socialists, or that they were always socialists. Some like Fred Mooney expressed socialist sentiments throughout their lives. Frank Keeney and others appealed to socialism much less after 1913 and even less so after Keeney’s split with Mother Jones in 1921. As a whole, black miners who supported the cause appear to have supported the Republican Party more than the socialist party in the long run. Why? Because the Republican Party had ended slavery and in racial matters was more civil rights-oriented while Democrats had the white southern vote. The socialists were at best muddy when it came to racial equality. Local direct actionists were often supportive of equality, but many boring withiners were less so.

When miners talked about their struggle, they often championed socialism. However, miners of all persuasions universally couched their cause in terms of constitutional and natural rights. They invoked God and the scriptures as support and justification for their struggle. They even, along with non-miner direct action socialists, joined the NRA to get discounts on mail-order guns and ammunition.

So–were the original rednecks socialist miners? Like all words redneck grew from local usage and its meaning changed with time, but given that widespread popular use begins with the coal wars, sure, that’s a supportable assertion. Early widespread use of the term referred to rural West Virginia miners. They were radicals and fighters. Many of them were direct-action socialists during a given time period. The groups overlap significantly but are not identical nor static.

In short though, GUN TOTING HILLBILLY REDNECK SOCIALIST RADICALS is a pretty accurate description as headlines go and it’s available as both a poster and t-shirt at Bullpush Merchantile.

—-

Support us on Patreon to read more of the historical details behind the Bullpush Hollow story.

Some Sources

(listing them all would go into the thousands):

July 1913 International Socialist Review

August 1913 International Socialist Review

The Commonwealth, April 18, 1913, (Everett, Washington) 1911-1914

On Boring from Within – Bert Russell | libcom.org

Betrayal in the West Virginia Coal Fields: Eugene V. Debs and the Socialist Party of America, 1912–1914 David Corbin The Journal of American History Vol. 64, No. 4 (Mar., 1978) , pp. 987-1009 https://www.jstor.org/stable/1890733

*Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: The Southern West Virginia Miners, 1880-1922 — David Corbin

The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom — James Green

**Transnational West Virginia: Ethnic Communities and Economic Change, 1840-1940 — Ken Fones-Wolf and Ronald Lewis, Eds.

The Speeches of Mother Jones — Edward Steel, Ed.

Struggle in the Coal Fields: The Autobiography of Fred Mooney

The Unexpected, Radical Roots of ‘Redneck’ | The Daily Yonder