Difficult Topics

This narrative often deals with difficult topics, and while it is written in the 2020s often deals with these topics from the perspective of a different time. The intent is to tell what happened and to tell it, as closely as possible, from the perspective of the miners of the early 1900s. The narrative focuses on them and may reflect language and views that are foreign to a modern reader. The topics, drama, feelings, and fight for liberty are relevant today and hopefully are moving. They are to us anyway.

As a forewarning, scenes of this history touch on race, class, civil rights, guns, politics, warfare, violence against women, pleas for freedom, capitalism, socialism, unions, independence, education, child labor, and more as seen through the lives and accounts of West Virginia miners and their families. The dealings of mine owners, politicians, and those in power will generally only be seen as they intersect directly with mine camp life rather than as they are planned and negotiated in the halls of power.

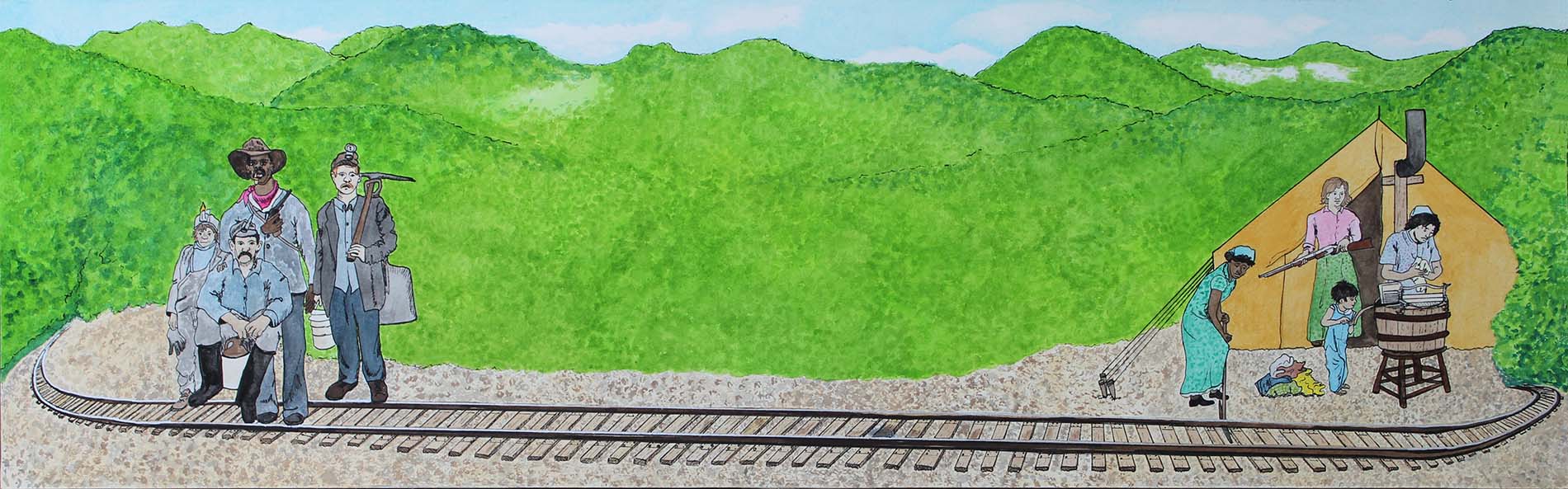

Some of the realities of mine life may seem unusual to the modern reader. Mine owners did not allow women to work in the mines, but male children could and did. Women were more likely to have a sixth or even eighth-grade education than men. Labor was divided between domestic and paid labor with both men and women sharing farming and gardening responsibilities. Men led the union locals when they formed and led the documented battle planning, but when it came to outright war women took up arms. We include these actions every time we find them documented.

Racial relations in the mines were different from those in the cities and farmland. Some non-union operators put more black men per shack than white men. In these mines black workers were more likely to be assigned to the hot work of the coke ovens.

At the same time, black miners, Italian miners, and white miners all held leadership positions in local unions and in the fight. Pay, such as it was, between miners was equal by the job rather than race. It wasn’t so much that things were better in the mines, but rather that everyone was mistreated equally. As CC Gillespie was wont to say “everyone’s black in the mines”. As George Echols, a former slave, testified before the senate: “I know the time when I was a slave and I feel just like we feel now.” Miners, of any race, weren’t generally welcome in Charleston.

That is not to say that there was not a degree of privilege in the wider public’s eye in being at least a white miner as opposed to a black or immigrant miner. Out-of-state newspapers often noted that the dead included white American miners in a disaster as an emphasis that this was actually a disaster. Also, if a family or individual was blackballed or managed to escape the mines, and then by work and sacrifice, obtained an education it was possible for white families to “pass” as non-miners within a generation and Italian or Eastern European families (not considered white at the time) within a couple of generations. Black miners and their families had no such opportunities, no matter how narrow, arduous or rare. They may eventually no longer be seen as miners, but they would still be subject to prejudice and discrimination based on race alone.

Either way, as long as you were a miner of any race, in real terms you and your family were disposable and bereft of civic and economic rights, including those of basic life and liberty. Miners often worked together equally in the mines and lived in the same housing. This and a common enemy brought a unity of cause to miners that transcended racial lines.

In matters of politics, organization, guns, violence, warfare, religion, and economic theories the story is the story. The politics of the day do not neatly line up with those of modernity. This story is messy, personal, and real.

We all have our own opinions on current events, and the events of the past should inform our understanding. In writing and illustrating, we’ve tried to focus on what happened and the views and experiences of West Virginians of the time. This particular work is intended to illuminate an important chapter of history and give voice to a people rather than to express our own opinions about history or current events. We hope that it will spark thought, consideration, widened perspectives, and considered action in the lives of our readers as it has for us.

John and Becky Glass