Bulllpush Hollow–An Online Historical Graphic Novel

updating with new strips Mondays & Thursdays

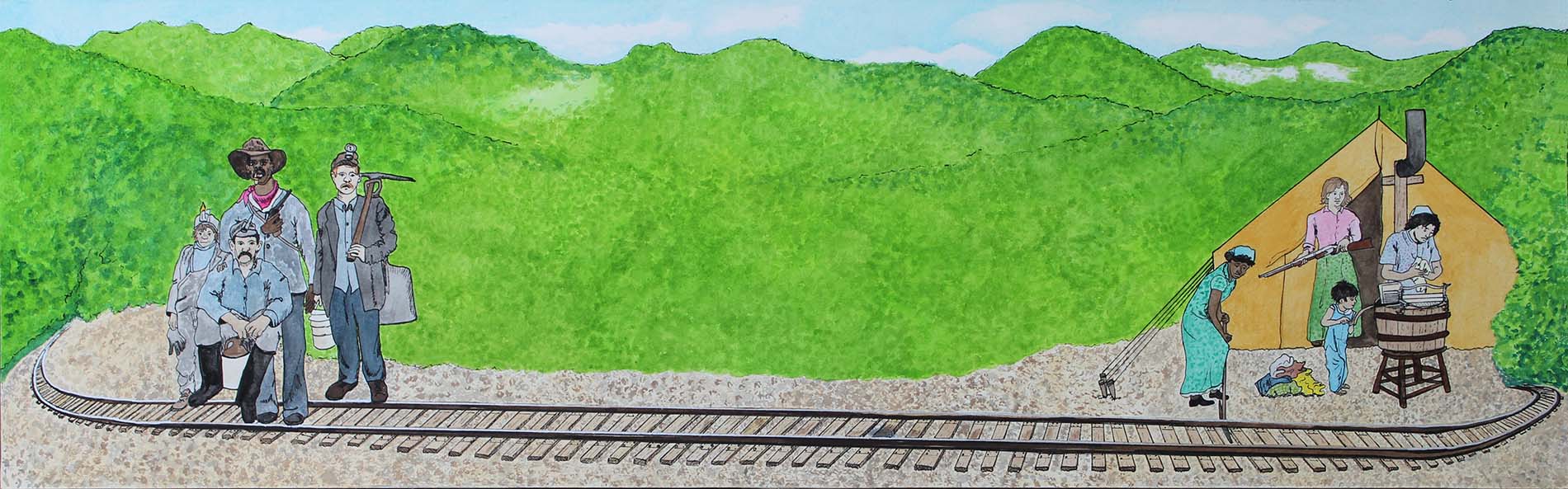

While young black children in the 1900s, for the most part, attended schools rather than working the mines, this was not the case during and immediately after the Civil War.

As soon as freedom was declared, Booker T. Washington’s stepfather* Washington Ferguson, who had never been able to live on the same plantation as his wife Jane, escaped and followed Union soldiers into the Kanawha Valley. When the Civil War ended, he sent for his family. Jane and her children, including Booker, “made the trip overland in a wagon, there being no railroad connection as yet with old Virginia.”

Booker first started working in the salt furnaces and soon thereafter began working in the mines. He was disappointed that his stepfather wanted him to work rather than attend school, and so attended at night or whenever he could. When he first appeared in school, the teacher asked his name. He replied Booker, as that was the only name he knew. And then realizing that others had both a first and a last name added his stepfather’s first name as his last identifying himself as Booker Washington and used that name ever since. What follows is a visualization of Booker’s own account of his time working in the mines. (Washington [Up from Slavery], Black Migration to Southern West Virginia by Joe Trotter in Transnational West Virginia edited by Fones-Wolf)

*stepfather for exactly the reasons you would expect for the son of an enslaved woman–she had been raped by a white man.

Kanawha Valley, 1866 or 1867

Out of Slavery and Into the Dark #5A

Extra story, history, news articles, and pictures available on Patreon!

Work in the coal-mine I always dreaded. One reason for this was that any one who worked in a coal-mine was always unclean, at least while at work, and it was a very hard job to get one’s skin clean after the day’s work was over. Then it was fully a mile from the opening of the coal-mine to the face of the coal, and all, of course, was in the blackest darkness. I do not believe that one ever experiences anywhere else such darkness as he does in a coal-mine. –Booker T. Washington

Booker’s cap was a “home job” that his mother sewed from scraps. In later years, he was proud that his mother refused to get him a store bought hat** that she could not afford and had the strength of character to live within her meager means.

**It seems that Dolly Parton’s Coat of Many Colors is appropriate here. Even now when I think of this song, I can’t help but hear my younger sister singing it when it was still popular from its first release.

—-

Before the advent of the carbide lamp, oil lamps which lit up only the area right before your face were used. This is the lighting method Booker would have had access to. Carbide lamps were first marketed in 1894, became common in the early 1900s, and declined in use by miners after a 1932 mine explosion where methane was believed to have been ignited by a lamp’s open flame.

Despite the claim in the ad below, electric lamps weren’t particularly popular before the 1930s. Battery technology still had a way to go in size, longevity, and cost when they first became available.