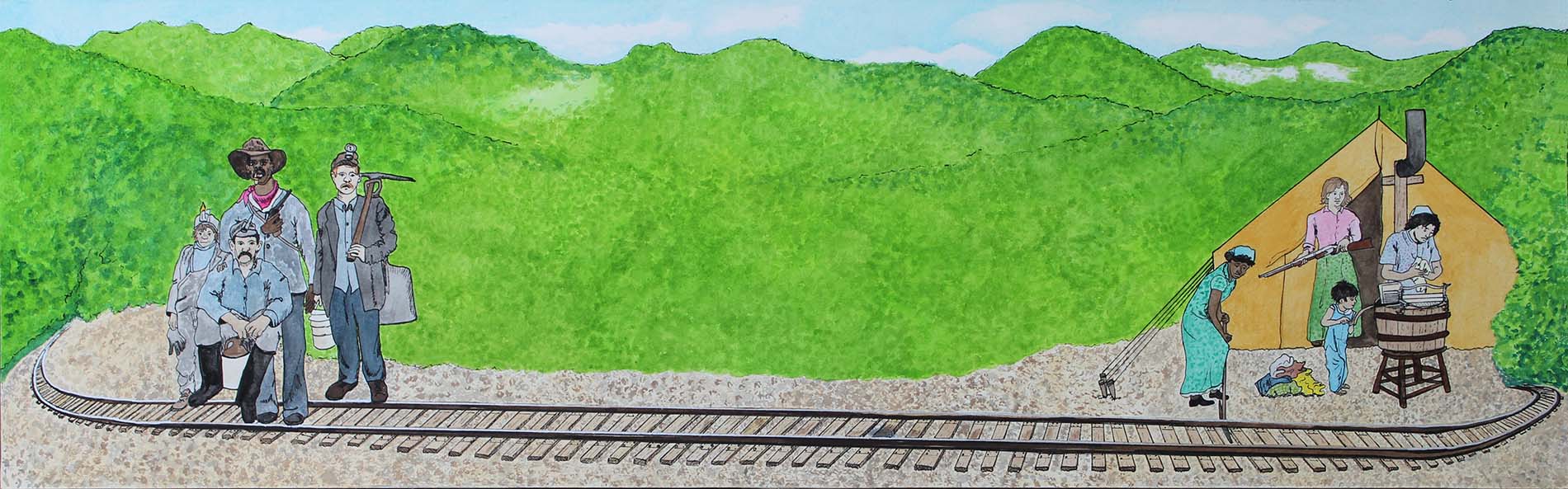

Bulllpush Hollow–An Online Historical Graphic Novel

updating with new strips Mondays & Thursdays

Sunday, Spring Bell Freewill Baptist Church

(Gillespie Oral History, Cavalier):

Church #4A

Soundtrack–In the Garden by Alan Jackson: Spotify

Extra story, history, news articles, and pictures available on Patreon!

Most miner churches couldn’t afford multiple songbooks. The churches in the Smithers area were of this type. Instead a chorister with a songbook would stand up front and ‘line out’ the lyrics by singing one phrase at a time and then pausing while the congregation sang the phrase back. (Gillespie Oral History, Cavalier)

Adult miners were not, by and large, a church going lot, but women and children were. Some miners, CC included, continued to be active in church throughout their lives. Mine owners subsidized the pay of preachers, and so, often held control over the particular teachings and flavor of worship–usually resulting in a very pro-company slant* to services. In response to this, many communities also had independent miner preachers who held services on Sundays that propounded a less corporate and usually more pro union brotherhood version of Christianity. (Corbin [Life], Gillespie Oral History, Green, others)

Many mining camps had dedicated church buildings, but there were none in Smithers area. In 1933 Ripley’s Believe It or Not listed Smithers as the only town of its size in the United States without a church building. Rather, church meetings were held in existing buildings built for other purposes. The Freewill Baptist Church rented the school house. Catholics rented the YMCA for Sunday services, but for lack of a priest likely held no local Mass. The First Baptist Church of Longacre, a black baptist church, started out meeting in a house and later met in ‘the little red schoolhouse’.

CC’s older brothers, at times, preached in the local Church of God which was led by miner preachers, but there is no indication of where they met. Generally, Italian immigrants were Catholic and Appalachian families that attended church, attended a local protestant congregation. When subsidized by owners, these congregations were segregated just as schools were. However, John Cavalier reports that the black Longacre First Baptist Choir was invited to perform regularly at various churches, both black and white, in the extended area. Masonic and other lodges were popular religious and social outlets for adult men; then again, so were saloons. (Cavalier, Gillespie Oral History)

Note: Margaret Gillespie Glass indicates that there was no segregation in her community with miners of all races living on the same streets and in the same neighborhoods. She does not mention integration or segregation of church specifically, but does mention a few individuals of various races (including Indian) being benefactors of or associated with the church in the early 1920’s. Cavalier goes into greater detail listing the town of Smithers as segregated. Margaret, in her notes on the book, does not comment on Cavalier’s assertions in this area. Smithers was an independent town that was next to the unsegregated coal camps–with Smithers, Cannelton, Longacre, Carbondale, and Bullpush all being very close together.

*Would you like a totally unbiased book expounding upon twenty objections to Christians belonging to labor unions? It just so happens that I have one to sell to you–cheap! The book is real, copyright 1924, but while we’re at it, I also have a bridge to sell you.